Visit us: Mon - Fri: 9:00 - 18:30

Braley Care Homes 6192 US 60 Hurricane, WV 25526

Experience Life at

Braley Care Homes

At Braley Care Homes, every day is filled with meaningful moments, engaging activities, and compassionate care. Our video collection offers a glimpse into the vibrant community we've built—where residents enjoy holiday celebrations, participate in enriching activities, and share their unique stories. Explore these videos to see how we create a warm, welcoming environment where seniors feel at home, supported, and celebrated.

Experience Life at

Braley Care Homes

At Braley Care Homes, every day is filled with meaningful moments, engaging activities, and compassionate care. Our video collection offers a glimpse into the vibrant community we've built—where residents enjoy holiday celebrations, participate in enriching activities, and share their unique stories. Explore these videos to see how we create a warm, welcoming environment where seniors feel at home, supported, and celebrated.

This Month’s Featured Insight

A Closer Look at Life at Braley Care Homes

🎉 Holiday Highlights & Festive Fun

🧠 Memory Care Moments & Tips

🎨 Everyday Adventures & Engaging Activities

💬 Heartfelt Stories & Resident Smiles

💡 Caregiver Corner: Wisdom & Wellness

Testimonials

I have only great memories of the great care my husband received. Never heard an unkind word to anyone there. This care home facility is wonderful. Thank you, Mr. Braley, for all you do and your staff. God's blessing continue to be with you all.

Brenda B. L.

I’ve worked there and I’ve seen how the residents are treated. Staff love their jobs and you can tell. Owner is great with residents too. They do a wide variety of activities and even a pet dog.

Samantha G.

I have only great memories of the great care my husband received. Never heard an unkind word to anyone there. This care home facility is wonderful. Thank you, Mr. Braley, for all you do and your staff. God's blessing continue to be with you all.

Brenda B. L.

I’ve worked there and I’ve seen how the residents are treated. Staff love their jobs and you can tell. Owner is great with residents too. They do a wide variety of activities and even a pet dog.

Samantha G.

Absolutely the best care home in the valley for your loved one with dementia.

Leah S. K.

Residents and workers are great. What you see is what you get. Thanks, BCH!

Nola H.

Absolutely the best care home in the valley for your loved one with dementia.

Leah S. K.

Residents and workers are great. What you see is what you get. Thanks, BCH!

Nola H.

Braley Care Homes

Caring Is Our Business

Read The Latest From Braley Care Homes

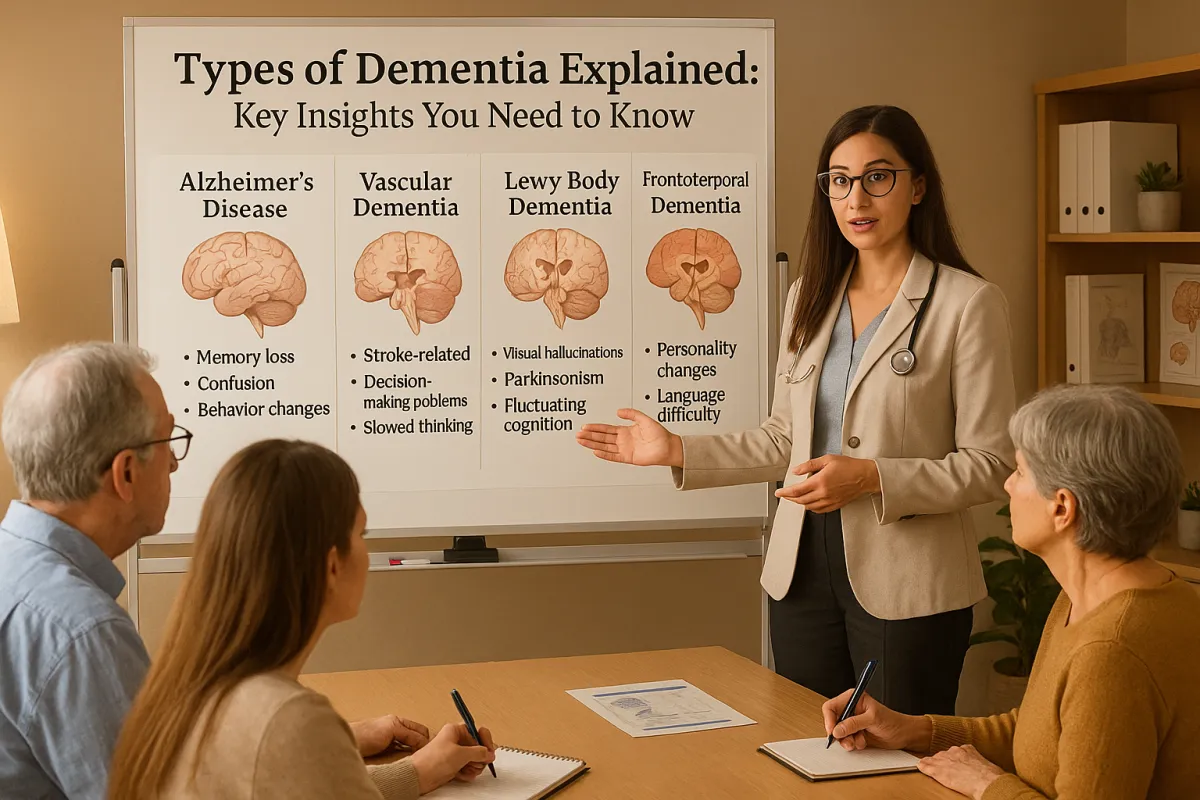

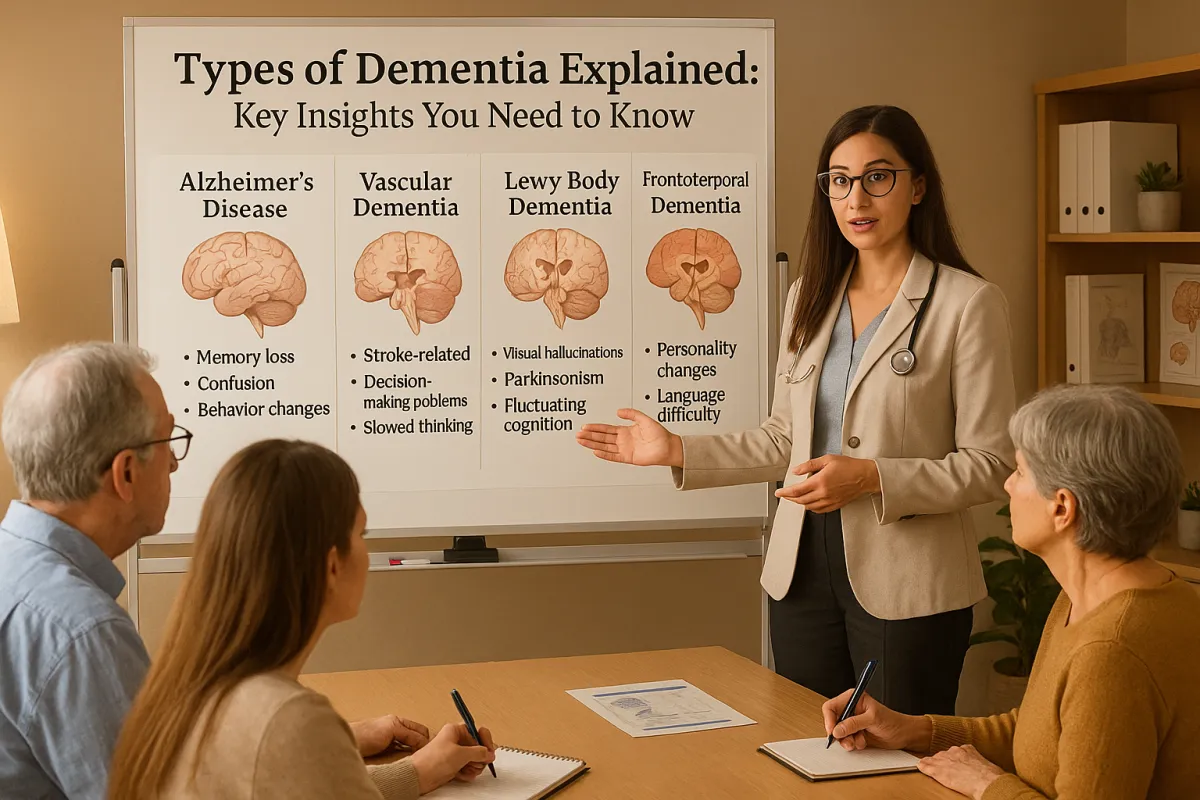

Types of Dementia Explained: Key Insights You Need to Know

Types of Dementia Explained: Understanding Symptoms, Causes, Treatments, and Care Strategies

Dementia represents one of the most challenging neurodegenerative disease conditions facing our ageing population, affecting millions of individuals and their families across West Virginia and throughout the United States. Understanding the various types of dementia, their unique characteristics, symptoms, and care requirements becomes essential for families navigating this complex landscape of cognitive decline and memory-related conditions that affect the central nervous system. While many people associate dementia exclusively with Alzheimer's disease, the reality encompasses a diverse spectrum of neurodegenerative conditions, each presenting distinct patterns of cognitive impairment, behavioral changes, and care needs that require specialized approaches to treatment and support from mental health professionals and geriatrics specialists.

The importance of understanding different dementia types extends far beyond academic knowledge, directly impacting the quality of care, treatment decisions, and daily management strategies that can significantly influence the well-being of individuals with cognitive impairments and their caregivers. For families in West Virginia seeking comprehensive memory care services, recognizing the specific type of dementia affecting their loved one enables more informed decisions about care options, from specialized assisted living programs to in-home support services that address the unique challenges associated with different forms of cognitive decline. Research from the National Institute on Aging and clinical trials published in The Lancet demonstrate that early identification and appropriate intervention can significantly impact life expectancy and quality of life for patients with various forms of dementia.

As the population ages and the prevalence of dementia continues to increase, the need for accurate information about symptoms, causes, treatments, and care strategies becomes increasingly critical for families, healthcare providers, and care facilities. The complexity of dementia diagnosis and management requires a thorough understanding of how different types of cognitive impairment manifest, progress, and respond to various therapeutic interventions and environmental modifications that can enhance quality of life for both patients and their families. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, proper diagnosis through medical imaging, neuroimaging, and comprehensive assessment by neurology and psychiatry specialists can help distinguish between various neurodegenerative diseases and identify potential risk factors such as cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and vitamin deficiency that may contribute to cognitive decline.

For families seeking specialized memory care services that understand the complexities of different dementia types, Braley Care Homes provides comprehensive dementia care programs designed to address the unique needs of individuals with various forms of cognitive impairment, offering professional oversight, specialized activities, and safe environments that promote comfort and dignity throughout the progression of memory-related conditions.

The journey of understanding dementia begins with recognizing that cognitive decline is not a normal part of aging, but rather represents specific disease processes that affect brain function in distinct ways. Each type of dementia involves different areas of the brain, follows unique patterns of progression, and requires tailored approaches to care that address the specific symptoms, behaviors, and functional limitations associated with that particular condition. This comprehensive understanding enables families to make informed decisions about care options, treatment approaches, and long-term planning that align with their loved one's specific needs and circumstances.

What Are the Main Types of Dementia?

Dementia encompasses a broad category of neurodegenerative conditions characterized by progressive cognitive decline that interferes with daily functioning, independence, and quality of life. While the term "dementia" is often used as a general descriptor, it actually represents an umbrella term covering numerous distinct conditions, each with unique underlying pathologies, symptom patterns, and progression trajectories that require specialized understanding and care approaches.

Alzheimer's disease stands as the most prevalent form of dementia, accounting for approximately 60-80% of all dementia cases and representing the condition most commonly associated with memory loss and cognitive decline in elderly individuals. This neurodegenerative condition primarily affects the hippocampus and other brain regions responsible for memory formation and retrieval, leading to the characteristic pattern of progressive memory loss, confusion, and eventual loss of ability to perform activities of daily living that defines the Alzheimer's experience.

Vascular dementia represents the second most common form of dementia, resulting from reduced blood flow to the brain due to stroke, small vessel disease, or other vascular conditions that compromise the brain's oxygen and nutrient supply. Unlike the gradual progression typical of Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia often presents with a stepwise decline in cognitive function, with periods of stability interrupted by sudden deteriorations that correspond to additional vascular events or the progression of underlying cardiovascular conditions.

Lewy body dementia, including both dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson's disease dementia, represents a complex condition characterized by the accumulation of abnormal protein deposits called Lewy bodies throughout the brain. This form of dementia presents unique challenges due to its combination of cognitive symptoms, movement disorders, visual hallucinations, and fluctuating levels of alertness and attention that can vary significantly from day to day or even hour to hour.

Frontotemporal dementia encompasses a group of conditions that primarily affect the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain, leading to changes in personality, behavior, and language function that often occur before significant memory loss becomes apparent. This type of dementia typically affects younger individuals, with onset often occurring between ages 40-65, and presents unique challenges for families due to the dramatic personality and behavioral changes that can strain relationships and complicate care planning.

Mixed dementia represents a condition where individuals experience features of multiple dementia types simultaneously, most commonly combining Alzheimer's disease with vascular dementia. This combination creates complex symptom patterns that may not fit neatly into a single diagnostic category and requires comprehensive assessment and individualized care approaches that address the multiple underlying pathologies contributing to cognitive decline.

Other less common forms of dementia include normal pressure hydrocephalus, which results from the accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid in the brain's ventricles; Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, a rare and rapidly progressive condition caused by prion proteins; Huntington's disease, a genetic condition that combines cognitive decline with movement disorders; and alcohol-related dementia, which results from chronic alcohol abuse and associated nutritional deficiencies that damage brain tissue over time.

The distinction between different dementia types becomes crucial for several reasons, including the development of appropriate treatment plans that address the specific underlying pathology and symptom patterns associated with each condition, the implementation of care strategies that accommodate the unique behavioral and functional challenges presented by different dementia types, the provision of accurate prognostic information that helps families plan for future care needs and make informed decisions about treatment options, and the identification of potential interventions that may slow progression or improve quality of life for specific dementia types.

Understanding the heterogeneity within dementia types also proves essential, as individuals with the same diagnosis may experience significantly different symptom patterns, rates of progression, and responses to treatment based on factors such as age of onset, overall health status, genetic factors, and environmental influences that can modify the expression and progression of neurodegenerative conditions.

What Is Alzheimer's Disease and Its Key Symptoms?

Alzheimer's disease represents the most well-known and extensively studied form of dementia, characterized by the progressive accumulation of abnormal protein deposits in the brain, including amyloid plaques and tau tangles that disrupt normal cellular function and communication between neurons in the central nervous system. This neurodegenerative disease typically begins with subtle changes in memory and cognition that may initially be attributed to normal ageing, but gradually progresses to severe cognitive impairment that significantly impacts all aspects of daily functioning and activities of daily living. Research from neuroscience studies and clinical trials shows that genetics, particularly the apolipoprotein E gene, along with risk factors such as cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and vitamin deficiency, can influence the development and progression of this condition that affects millions of patients worldwide.

The pathological hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease involve the accumulation of beta-amyloid protein fragments that form amyloid plaques between nerve cells, and the development of tau protein tangles within neurons that disrupt the cellular transport system and lead to widespread cell death throughout the nervous system. These pathological changes typically begin years or even decades before symptoms become apparent, starting in the hippocampus and gradually spreading to other lobes of the brain responsible for language, reasoning, and social behavior. Medical imaging and neuroimaging studies, including positron emission tomography scans, can now detect these changes in living patients, allowing for earlier diagnosis and intervention according to research published in medicine journals and systematic reviews.

Early-stage Alzheimer's disease symptoms often manifest as mild cognitive impairment that may include difficulty remembering recent events, conversations, or appointments while retaining clear memories of distant past events, a pattern that reflects the progressive damage to neurons responsible for learning and memory formation. Individuals may experience challenges with executive functions, problem-solving, planning, and completing familiar tasks, such as managing finances, following recipes, or navigating to familiar locations. Language difficulties may emerge, including trouble finding the right words, following conversations, or understanding written instructions, while judgement and insight into their own cognitive changes may become impaired. Mental health professionals and geriatrics specialists often note that patients may develop major depressive disorder or anxiety as they become aware of their cognitive decline, requiring comprehensive assessment by psychology and psychiatry experts.

As Alzheimer's disease progresses to moderate stages, memory loss becomes more pronounced and begins to interfere significantly with activities of daily living and independence. Individuals may forget important personal information, become confused about time and place, and require assistance with basic self-care tasks such as dressing, bathing, and meal preparation. Behavioral changes may become apparent, including increased anxiety, psychomotor agitation, wandering, and sleep disturbances that can be challenging for both patients and caregivers. Some patients may develop psychosis, including hallucinations or delusions, while others may experience delirium during acute medical illnesses, requiring careful evaluation by mental health professionals to distinguish between these conditions and the underlying dementia progression.

Advanced Alzheimer's disease involves severe cognitive impairment that affects all aspects of functioning, including the loss of ability to communicate effectively, recognize family members, or perform basic self-care tasks. Individuals may experience significant personality changes, become increasingly dependent on others for all aspects of care, and develop complications related to immobility, muscle weakness, swallowing difficulties, and increased susceptibility to infections such as aspiration pneumonia. At this stage, palliative care approaches become important to maintain comfort and dignity, while families may need to consider end-of-life planning as life expectancy becomes limited according to research on disease progression and outcomes.

The progression of Alzheimer's disease varies significantly among individuals, with some experiencing rapid decline over a few years while others maintain relatively stable functioning for extended periods. Factors that may influence progression include age of onset (with early onset dementia often progressing more rapidly), overall health status, educational background, social support systems, and access to appropriate medical care and interventions that may help slow cognitive decline. Research indicates that risk factors such as cardiovascular disease, hypertension, obesity, substance abuse, and vitamin deficiency (particularly vitamin B12 deficiency, vitamin D deficiency, and thiamine deficiency) can accelerate progression, while protective factors like physical activity, healthy diet including olive oil, and mental stimulation may help preserve cognition longer.

How Does Vascular Dementia Develop and What Causes It?

Vascular dementia represents the second most common form of neurodegenerative disease, resulting from reduced blood flow to the brain due to damage to blood vessels that supply oxygen and nutrients to brain tissue. This condition develops when cardiovascular disease, atherosclerosis, hypertension, or other vascular conditions compromise the brain's blood supply, leading to areas of brain tissue death and subsequent cognitive impairment that affects millions of patients worldwide according to research from neurology and geriatrics specialists.

The development of vascular dementia typically involves damage to small blood vessels in the brain, often called small vessel disease, which can cause multiple small strokes or areas of chronic ischemia that gradually accumulate over time. Unlike the gradual progression characteristic of Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia often presents with a stepwise decline in cognitive function, with periods of stability interrupted by sudden deteriorations that correspond to additional vascular events or the progression of underlying cardiovascular conditions affecting the central nervous system.

Risk factors for vascular dementia closely mirror those for cardiovascular disease and include hypertension, which represents the most significant modifiable risk factor for developing vascular cognitive impairment, diabetes mellitus, which damages blood vessels throughout the body including those in the brain, atherosclerosis and other forms of cardiovascular disease that reduce blood flow to brain tissue, smoking, which damages blood vessels and increases stroke risk, and obesity, which contributes to multiple cardiovascular risk factors that can affect brain health.

The pathophysiology of vascular dementia involves multiple mechanisms of brain injury, including large strokes that cause obvious neurological symptoms and cognitive impairment, multiple small strokes (lacunar infarcts) that may go unnoticed individually but accumulate to cause significant cognitive decline, chronic hypoperfusion that gradually damages brain tissue without causing obvious strokes, and small vessel disease that affects the white matter connections between different brain regions essential for cognitive function.

Medical imaging and neuroimaging studies play a crucial role in diagnosing vascular dementia, with computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging revealing evidence of strokes, white matter changes, and other vascular pathology that correlates with cognitive symptoms. Advanced neuroimaging techniques can detect subtle changes in blood flow and brain structure that may not be apparent on routine scans but contribute to cognitive impairment in patients with vascular risk factors.

The cognitive symptoms of vascular dementia can vary significantly depending on the location and extent of vascular damage, but commonly include executive dysfunction that affects planning, problem-solving, and decision-making abilities, attention and concentration problems that may fluctuate throughout the day, processing speed deficits that make thinking and responding slower than normal, and memory problems that may be less prominent than in Alzheimer's disease but still significantly impact daily functioning and activities of daily living.

Prevention of vascular dementia focuses on managing cardiovascular risk factors through lifestyle modifications and medical treatment, including blood pressure control through medication and lifestyle changes, diabetes management to prevent vascular complications, cholesterol management through diet and statin medications, smoking cessation to reduce vascular damage, regular physical activity to improve cardiovascular health, and maintaining a healthy diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and omega-3 fatty acids that support vascular health.

The prognosis for vascular dementia varies depending on the underlying vascular pathology and the success of interventions to prevent additional vascular events. Unlike some other forms of dementia, vascular dementia progression may be slowed or even stabilized through aggressive management of cardiovascular risk factors, making early identification and intervention particularly important for preserving cognitive function and quality of life.

What Are the Characteristics of Lewy Body Dementia?

Dementia with Lewy bodies represents a complex neurodegenerative disease characterized by the accumulation of abnormal protein deposits called Lewy bodies throughout the brain, particularly in the cerebral cortex and other regions of the central nervous system. This condition, also known as Lewy body dementia, presents unique challenges due to its combination of cognitive symptoms, movement disorders similar to Parkinson's disease, visual hallucinations, and fluctuating levels of alertness and attention that can vary significantly from day to day or even hour to hour, affecting millions of patients worldwide according to neurology and psychiatry research.

The pathological hallmarks of dementia with Lewy bodies involve the accumulation of alpha-synuclein protein aggregates that form Lewy bodies within neurons throughout the nervous system, leading to progressive cell death and dysfunction in multiple brain regions. These protein deposits affect neurotransmitter systems, particularly dopamine and acetylcholine, which explains the combination of movement problems and cognitive symptoms that characterize this neurodegenerative disease according to neuroscience studies and systematic reviews published in medicine journals.

The core clinical features of dementia with Lewy bodies include fluctuating cognition with pronounced variations in attention and alertness that may be mistaken for delirium or other acute medical conditions, recurrent complex visual hallucinations that are typically well-formed and detailed, often involving people or animals that appear real to the patient, and spontaneous features of parkinsonism including bradykinesia (slowness of movement), rigidity, tremor, and postural instability that may develop before or after cognitive symptoms appear.

Cognitive symptoms in dementia with Lewy bodies often include prominent deficits in executive functions, attention, and visual-spatial processing, while memory problems may be less severe than in Alzheimer's disease, particularly in the early stages. Patients may experience significant difficulties with activities of daily living due to the combination of cognitive impairment and movement problems, requiring specialized care approaches that address both aspects of the condition.

The fluctuating nature of dementia with Lewy bodies represents one of its most distinctive and challenging features, with patients experiencing periods of relative clarity and alertness alternating with episodes of confusion, disorientation, and reduced responsiveness. These fluctuations can occur over hours, days, or weeks, making it difficult for families and caregivers to predict the patient's functional abilities and plan appropriate activities and care interventions.

Visual hallucinations in dementia with Lewy bodies are typically complex and well-formed, often involving people, animals, or objects that appear real and detailed to the patient. These hallucinations may be distressing or benign, and patients may retain some insight into their unreality, particularly in the early stages of the condition. The management of hallucinations requires careful consideration, as traditional antipsychotic medications can cause severe worsening of movement symptoms and should generally be avoided in this population.

Sleep disorders are common in dementia with Lewy bodies, particularly REM sleep behavior disorder, where patients act out their dreams during sleep, potentially causing injury to themselves or their bed partners. This sleep disorder may precede other symptoms of dementia with Lewy bodies by years or decades, making it an important early marker of the condition that may allow for earlier diagnosis and intervention.

Autonomic dysfunction frequently accompanies dementia with Lewy bodies and can include orthostatic hypotension (drop in blood pressure when standing), constipation, urinary incontinence, and temperature regulation problems that can significantly impact quality of life and safety. These autonomic symptoms may require specific medical management and environmental modifications to prevent complications such as falls and injuries.

The diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies requires careful clinical assessment by neurology and psychiatry specialists, as the condition can be challenging to distinguish from other forms of dementia, particularly Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease dementia. Specialized neuroimaging studies, including dopamine transporter scans, may help support the diagnosis by revealing reduced dopamine function in the brain regions affected by Lewy body pathology.

Treatment of dementia with Lewy bodies requires a multidisciplinary approach that addresses the complex constellation of cognitive, motor, and psychiatric symptoms while avoiding medications that can worsen the condition. Cholinesterase inhibitors may be particularly beneficial for cognitive symptoms and hallucinations, while careful use of levodopa may help with movement problems, though patients with dementia with Lewy bodies may be more sensitive to medication side effects than those with Parkinson's disease alone.

What Other Less Common Types of Dementia Should You Know?

Beyond the more prevalent forms of dementia such as Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia, and dementia with Lewy bodies, several less common but significant types of cognitive impairment deserve attention due to their unique characteristics, treatment approaches, and impact on individuals and families. Understanding these conditions becomes important for accurate diagnosis, appropriate treatment planning, and realistic expectations about progression and care needs, particularly when patients present with atypical symptoms or early onset dementia that may suggest alternative diagnoses.

Frontotemporal dementia represents a group of neurodegenerative diseases that primarily affect the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain, leading to changes in personality, behavior, and language that often occur before significant memory problems become apparent. This form of dementia typically affects younger individuals, with onset commonly occurring between ages 40-65, making it particularly devastating for families as it strikes during peak productive years when individuals may still be working and raising children. The condition involves progressive cell death in specific brain regions, often related to abnormal protein accumulations including tau, TDP-43, or other proteins that disrupt normal cellular function.

The behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia involves dramatic changes in personality and social behavior, including loss of empathy, inappropriate social conduct, impulsivity, and repetitive behaviors that can strain family relationships and create significant caregiving challenges. Individuals may lose their ability to understand social cues, engage in inappropriate sexual or aggressive behavior, or develop obsessive interests that dominate their daily activities, requiring specialized management approaches from mental health professionals and geriatrics specialists.

Primary progressive aphasia, another form of frontotemporal dementia, primarily affects language function while initially preserving other cognitive abilities. This condition can manifest as difficulty finding words, understanding speech, or producing grammatically correct sentences, gradually progressing to more severe communication impairments that significantly impact social interaction and daily functioning. The condition affects the lobes of the brain responsible for language processing, leading to progressive deterioration in communication abilities while other cognitive functions may remain relatively intact.

Normal pressure hydrocephalus represents a potentially treatable form of dementia caused by the accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid in the brain's ventricles, leading to increased pressure that affects cognitive function, walking ability, and bladder control. The classic triad of symptoms includes cognitive impairment, gait disturbance, and urinary incontinence, though not all individuals present with all three features. Medical imaging and neuroimaging studies can reveal the characteristic enlargement of ventricles that suggests this diagnosis, making it crucial to consider in the evaluation of cognitive decline, particularly in older adults.

The importance of recognizing normal pressure hydrocephalus lies in its potential treatability through surgical placement of a shunt to drain excess cerebrospinal fluid, which may lead to improvement in symptoms if the condition is identified and treated appropriately. Unlike other neurodegenerative diseases, this condition may be partially reversible with appropriate intervention, making early recognition and treatment particularly important for preserving cognitive function and quality of life.

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease represents a rare but rapidly progressive form of dementia caused by prion proteins that lead to spongiform changes in brain tissue and widespread cell death throughout the central nervous system. This condition typically progresses much more rapidly than other forms of dementia, with most individuals surviving only months to a few years after symptom onset. The rapid progression and unique pathology make this condition particularly challenging for families and care providers, requiring specialized palliative care approaches to maintain comfort and dignity.

Huntington's disease involves a genetic mutation that leads to progressive degeneration of nerve cells in the brain, causing a combination of cognitive decline, movement disorders, and psychiatric symptoms. The hereditary nature of this condition raises important considerations for family planning and genetic counseling, as children of affected individuals have a 50% chance of inheriting the genetic mutation. The condition affects multiple brain regions and neurotransmitter systems, leading to a complex constellation of symptoms that require multidisciplinary care approaches.

Alcohol-related dementia results from chronic substance abuse and associated nutritional deficiencies, particularly thiamine deficiency and vitamin B12 deficiency, that damage brain tissue over time and lead to cognitive impairment. This condition may be partially reversible with alcohol cessation and appropriate nutritional supplementation, including thiamine, vitamin B12, vitamin D, and other essential nutrients, though complete recovery is uncommon once significant cognitive impairment has developed.

Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome represents a specific form of alcohol-related brain damage that combines acute confusion and eye movement problems (Wernicke encephalopathy) with severe memory impairment and confabulation (Korsakoff's syndrome). Early recognition and treatment with thiamine supplementation may prevent progression to the chronic memory problems characteristic of Korsakoff's syndrome, highlighting the importance of identifying and treating vitamin deficiency in patients with substance abuse histories.

Other medical conditions that can cause dementia-like symptoms include brain tumor, subdural hematoma, hypoglycemia, malnutrition, and various metabolic disorders that affect brain function. These conditions may be reversible with appropriate treatment, making comprehensive medical evaluation essential for any patient presenting with cognitive decline to rule out treatable causes before attributing symptoms to neurodegenerative disease.

Childhood dementia represents a rare but devastating group of conditions that affect children and adolescents, often involving genetic disorders that cause progressive cognitive decline and neurological deterioration. These conditions require specialized pediatric neurology care and present unique challenges for families dealing with cognitive decline in young individuals who should be developing rather than losing cognitive abilities.

Posterior cortical atrophy represents a variant of Alzheimer's disease that primarily affects the visual processing areas of the brain, leading to difficulties with visual perception, spatial processing, and reading while initially preserving memory function. This condition can be particularly challenging to diagnose as patients may present with visual symptoms rather than typical memory problems, requiring specialized neuropsychological assessment and neuroimaging to identify the underlying pathology.

Vascular dementia develops as a result of reduced blood flow to the brain, which can occur through various mechanisms including stroke, small vessel disease, or other cardiovascular conditions that compromise the brain's ability to receive adequate oxygen and nutrients necessary for normal cellular function. Unlike Alzheimer's disease, which involves the gradual accumulation of abnormal proteins, vascular dementia results from damage to the brain's blood vessels and the subsequent death of brain tissue in areas deprived of adequate circulation.

The most common cause of vascular dementia involves small strokes or transient ischemic attacks that may go unnoticed but cumulatively damage brain tissue over time. These "silent strokes" often affect small blood vessels deep within the brain, leading to multiple small areas of tissue death that gradually impair cognitive function. The pattern of cognitive decline in vascular dementia often reflects the specific brain regions affected by vascular damage, leading to a more variable presentation compared to the relatively predictable progression seen in Alzheimer's disease.

Large strokes that affect significant portions of the brain can also lead to vascular dementia, particularly when they involve areas crucial for cognitive function such as the frontal lobes, which are responsible for executive function, planning, and decision-making. Post-stroke dementia may develop immediately following a major stroke or may emerge gradually as the brain attempts to compensate for damaged areas and additional vascular events occur over time.

Small vessel disease represents another important cause of vascular dementia, involving the gradual narrowing and damage of small blood vessels throughout the brain due to conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and atherosclerosis. This process leads to chronic reduced blood flow that may not cause obvious stroke symptoms but gradually impairs cognitive function through the cumulative effects of chronic oxygen deprivation and the development of white matter lesions visible on brain imaging studies.

Risk factors for vascular dementia closely mirror those for cardiovascular disease and include hypertension, diabetes mellitus, high cholesterol, smoking, obesity, and sedentary lifestyle. These modifiable risk factors suggest that vascular dementia may be more preventable than other forms of dementia through appropriate management of cardiovascular health and lifestyle modifications that promote healthy blood flow to the brain.

The symptoms of vascular dementia can vary significantly depending on the location and extent of vascular damage, but commonly include difficulties with executive function, attention, and processing speed rather than the memory problems that characterize early Alzheimer's disease. Individuals with vascular dementia may experience problems with planning, organizing, and completing tasks, along with slowed thinking and difficulty concentrating on complex activities.

The progression of vascular dementia often follows a stepwise pattern, with periods of relative stability interrupted by sudden declines that correspond to additional vascular events. This pattern differs from the gradual, steady decline typically seen in Alzheimer's disease and may provide opportunities for stabilization or even modest improvement with appropriate medical management of underlying vascular conditions.

Physical symptoms may accompany cognitive changes in vascular dementia, including weakness, difficulty walking, balance problems, and changes in speech or swallowing that reflect the broader impact of vascular disease on brain function. These physical manifestations can help distinguish vascular dementia from other forms of cognitive impairment and guide appropriate treatment approaches.

The diagnosis of vascular dementia relies heavily on brain imaging studies that can reveal evidence of stroke, small vessel disease, or other vascular pathology, along with clinical assessment of cognitive function and careful review of medical history to identify vascular risk factors and previous cerebrovascular events. The timing of cognitive decline in relation to vascular events provides important diagnostic clues that help differentiate vascular dementia from other forms of cognitive impairment.

Treatment approaches for vascular dementia focus primarily on managing underlying vascular risk factors to prevent additional brain damage, including aggressive control of blood pressure, diabetes, and cholesterol levels, along with lifestyle modifications such as regular exercise, healthy diet, and smoking cessation. While these interventions may not reverse existing cognitive impairment, they can potentially slow progression and reduce the risk of additional vascular events that could worsen cognitive function.

What Are the Characteristics of Lewy Body Dementia?

Lewy body dementia represents a complex and often misunderstood form of dementia characterized by the presence of abnormal protein deposits called Lewy bodies throughout the brain, leading to a unique constellation of cognitive, motor, and psychiatric symptoms that can fluctuate significantly over time. This condition encompasses both dementia with Lewy bodies, where cognitive symptoms appear first, and Parkinson's disease dementia, where movement problems precede cognitive decline, though both conditions share similar underlying pathology and clinical features.

The hallmark feature of Lewy body dementia involves significant fluctuations in cognitive function, alertness, and attention that can vary dramatically from day to day or even hour to hour. Individuals may appear relatively normal and engaged during certain periods, only to become confused, disoriented, or unresponsive hours later, creating challenges for both diagnosis and care planning as these fluctuations can be mistaken for other conditions or attributed to external factors.

Visual hallucinations represent another characteristic feature of Lewy body dementia, typically involving well-formed, detailed images of people, animals, or objects that appear real to the individual experiencing them. These hallucinations are usually not threatening or disturbing, and individuals may maintain insight into their unreality, though this awareness may fluctuate along with other cognitive symptoms. The presence of visual hallucinations early in the course of cognitive decline strongly suggests Lewy body dementia rather than Alzheimer's disease.

Movement disorders similar to those seen in Parkinson's disease commonly accompany Lewy body dementia, including tremor, rigidity, slow movement, and balance problems that increase the risk of falls and complicate daily activities. These motor symptoms may respond to medications used to treat Parkinson's disease, though individuals with Lewy body dementia often show increased sensitivity to antipsychotic medications that can worsen movement problems and cognitive function.

Sleep disturbances represent a prominent feature of Lewy body dementia, particularly REM sleep behavior disorder, where individuals act out their dreams during sleep, potentially leading to injury to themselves or their bed partners. Other sleep problems may include excessive daytime sleepiness, insomnia, and disrupted sleep-wake cycles that can exacerbate cognitive symptoms and behavioral problems.

Cognitive symptoms in Lewy body dementia often involve executive function, attention, and visual-spatial processing more prominently than memory, particularly in the early stages of the condition. Individuals may experience difficulty with planning, problem-solving, and multitasking, along with problems interpreting visual information and navigating familiar environments. Memory problems may be less prominent initially compared to Alzheimer's disease, though they typically develop as the condition progresses.

Autonomic dysfunction commonly occurs in Lewy body dementia, affecting the nervous system's control of automatic bodily functions such as blood pressure regulation, temperature control, and digestive function. This can lead to symptoms such as orthostatic hypotension (drop in blood pressure when standing), constipation, urinary problems, and temperature regulation difficulties that can significantly impact quality of life and safety.

The diagnosis of Lewy body dementia can be challenging due to the fluctuating nature of symptoms and the overlap with other conditions such as Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease. Specialized imaging studies, including DaTscan, can help identify the dopamine system abnormalities characteristic of Lewy body conditions, while careful clinical assessment of the timing and pattern of symptoms provides important diagnostic information.

Treatment of Lewy body dementia requires a careful balance of medications to address cognitive symptoms, movement problems, and psychiatric features while avoiding drugs that can worsen the condition. Cholinesterase inhibitors used to treat Alzheimer's disease may be particularly beneficial for cognitive symptoms and hallucinations in Lewy body dementia, while medications for movement problems must be used cautiously due to increased sensitivity to side effects.

The complex and fluctuating nature of Lewy body dementia creates unique challenges for caregivers, who must adapt to rapidly changing symptoms and needs while managing the uncertainty and unpredictability that characterizes this condition. Understanding the specific features of Lewy body dementia enables families and care providers to develop appropriate strategies for managing symptoms and maintaining safety while preserving quality of life throughout the progression of the condition.

For families dealing with the complex challenges of Lewy body dementia and other forms of cognitive impairment, Braley Care Homes offers specialized memory care programs with trained staff who understand the unique needs of individuals with different types of dementia, providing safe environments and appropriate activities that accommodate fluctuating symptoms and complex care requirements.

What Other Less Common Types of Dementia Should You Know?

Beyond the more prevalent forms of dementia such as Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia, and Lewy body dementia, several less common but significant types of cognitive impairment deserve attention due to their unique characteristics, treatment approaches, and impact on individuals and families. Understanding these conditions becomes important for accurate diagnosis, appropriate treatment planning, and realistic expectations about progression and care needs.

Frontotemporal dementia represents a group of conditions that primarily affect the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain, leading to changes in personality, behavior, and language that often occur before significant memory problems become apparent. This form of dementia typically affects younger individuals, with onset commonly occurring between ages 40-65, making it particularly devastating for families as it strikes during peak productive years when individuals may still be working and raising children.

The behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia involves dramatic changes in personality and social behavior, including loss of empathy, inappropriate social conduct, impulsivity, and repetitive behaviors that can strain family relationships and create significant caregiving challenges. Individuals may lose their ability to understand social cues, engage in inappropriate sexual or aggressive behavior, or develop obsessive interests that dominate their daily activities.

Primary progressive aphasia, another form of frontotemporal dementia, primarily affects language function while initially preserving other cognitive abilities. This condition can manifest as difficulty finding words, understanding speech, or producing grammatically correct sentences, gradually progressing to more severe communication impairments that significantly impact social interaction and daily functioning.

Normal pressure hydrocephalus represents a potentially treatable form of dementia caused by the accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid in the brain's ventricles, leading to increased pressure that affects cognitive function, walking ability, and bladder control. The classic triad of symptoms includes cognitive impairment, gait disturbance, and urinary incontinence, though not all individuals present with all three features.

The importance of recognizing normal pressure hydrocephalus lies in its potential treatability through surgical placement of a shunt to drain excess cerebrospinal fluid, which may lead to improvement in symptoms if the condition is identified and treated appropriately. Brain imaging studies can reveal the characteristic enlargement of ventricles that suggests this diagnosis, making it crucial to consider in the evaluation of cognitive decline.

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease represents a rare but rapidly progressive form of dementia caused by prion proteins that lead to spongiform changes in brain tissue. This condition typically progresses much more rapidly than other forms of dementia, with most individuals surviving only months to a few years after symptom onset. The rapid progression and unique pathology make this condition particularly challenging for families and care providers.

Huntington's disease involves a genetic mutation that leads to progressive degeneration of nerve cells in the brain, causing a combination of cognitive decline, movement disorders, and psychiatric symptoms. The hereditary nature of this condition raises important considerations for family planning and genetic counseling, as children of affected individuals have a 50% chance of inheriting the genetic mutation.

Alcohol-related dementia results from chronic alcohol abuse and associated nutritional deficiencies, particularly thiamine deficiency, that damage brain tissue over time. This condition may be partially reversible with alcohol cessation and appropriate nutritional supplementation, though complete recovery is uncommon once significant cognitive impairment has developed.

Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome represents a specific form of alcohol-related brain damage that combines acute confusion and eye movement problems (Wernicke's encephalopathy) with severe memory impairment and confabulation (Korsakoff's syndrome). Early recognition and treatment with thiamine supplementation may prevent progression to the chronic memory problems characteristic of Korsakoff's syndrome.

HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder can occur in individuals with HIV infection, particularly those with advanced disease or inadequate treatment. The widespread use of effective antiretroviral therapy has significantly reduced the incidence of severe HIV-related dementia, though milder cognitive impairments may still occur and require ongoing monitoring and management.

Traumatic brain injury can lead to chronic cognitive impairment and dementia, particularly in individuals who have experienced repeated head injuries such as athletes in contact sports or military personnel exposed to blast injuries. The relationship between traumatic brain injury and later development of dementia continues to be an active area of research with important implications for prevention and treatment.

The recognition of these less common dementia types becomes important for several reasons, including the identification of potentially treatable conditions such as normal pressure hydrocephalus that may improve with appropriate intervention, the provision of accurate prognostic information that helps families understand the expected course and timeline of the condition, the implementation of appropriate care strategies that address the specific symptoms and challenges associated with each condition, and the consideration of genetic counseling and family planning issues for hereditary conditions such as Huntington's disease.

Understanding the diversity of dementia types also highlights the importance of comprehensive evaluation by specialists who can distinguish between different conditions and develop appropriate treatment plans that address the specific underlying pathology and symptom patterns associated with each form of cognitive impairment.

What Are the Early Signs of Dementia to Watch For?

Recognizing the early signs of dementia represents a critical step in obtaining timely diagnosis and appropriate care, yet the subtle nature of initial symptoms often leads to delays in seeking medical attention as changes may be attributed to normal aging, stress, or other factors. Understanding the distinction between normal age-related changes and early dementia symptoms enables families to seek appropriate evaluation and support when concerns arise.

The early signs of dementia can vary significantly depending on the specific type of cognitive impairment and the brain regions initially affected, but certain patterns of change should prompt further evaluation by healthcare professionals. Memory problems represent the most commonly recognized early sign, though the specific pattern of memory loss can provide important clues about the underlying condition.

In Alzheimer's disease, early memory problems typically involve difficulty remembering recent events, conversations, or appointments while maintaining clear recollection of distant memories. Individuals may repeat questions or stories, forget important dates or events, or require increasing reliance on memory aids such as notes or reminders to manage daily activities that were previously handled automatically.

However, memory loss is not always the first or most prominent symptom in other forms of dementia. Frontotemporal dementia may initially present with personality changes, inappropriate social behavior, or language difficulties while memory remains relatively intact. Lewy body dementia may begin with visual hallucinations, movement problems, or fluctuating attention rather than obvious memory impairment.

Changes in executive function, including difficulty with planning, organizing, and problem-solving, often represent early signs of dementia that may be overlooked or attributed to other factors. Individuals may struggle with tasks that require multiple steps, such as managing finances, following recipes, or organizing household activities that were previously routine and automatic.

Language difficulties can manifest as early signs of dementia, including trouble finding the right words, following conversations, or understanding written instructions. These changes may initially be subtle, such as pausing to search for common words or using vague terms instead of specific names for objects or people.

Changes in judgment and decision-making ability may become apparent through poor financial decisions, inappropriate social behavior, or neglect of personal hygiene and safety. These changes can be particularly concerning when they represent a significant departure from the individual's previous personality and behavior patterns.

Spatial and visual processing problems may manifest as difficulty navigating familiar routes, problems with depth perception, or challenges interpreting visual information. Individuals may become lost in familiar places, have trouble parking or judging distances, or experience difficulty reading or recognizing faces.

Mood and personality changes often accompany early dementia, including increased anxiety, depression, irritability, or apathy that may be mistaken for other mental health conditions. These changes may represent the individual's response to awareness of cognitive decline or may result from the direct effects of brain changes on emotional regulation.

Sleep disturbances, including changes in sleep patterns, excessive daytime sleepiness, or acting out dreams during sleep, can represent early signs of certain types of dementia, particularly Lewy body dementia. These sleep problems may precede other cognitive symptoms by months or years.

Social withdrawal and loss of interest in previously enjoyed activities may occur as individuals become aware of their cognitive difficulties and feel embarrassed or frustrated by their changing abilities. This withdrawal can accelerate cognitive decline by reducing social stimulation and mental engagement that help maintain cognitive function.

How Can Memory Loss Indicate Dementia?

Memory loss represents the most widely recognized symptom of dementia, yet understanding the specific patterns and characteristics of memory impairment can provide important insights into the type and severity of cognitive decline. Not all memory problems indicate dementia, and the distinction between normal age-related memory changes and pathological memory loss requires careful evaluation of the pattern, severity, and impact on daily functioning.

Normal aging involves some decline in certain types of memory, particularly the ability to quickly recall names, words, or specific details, but these changes typically do not interfere significantly with daily activities or independence. Older adults may experience occasional difficulty remembering where they placed items, the names of acquaintances, or specific details of recent events, but they generally retain the ability to learn new information and remember important personal and historical information.

Pathological memory loss associated with dementia differs from normal aging in several important ways, including the severity and persistence of memory problems that interfere with daily activities and independence, the pattern of memory loss that affects recent events more than distant memories, particularly in Alzheimer's disease, the inability to learn and retain new information despite repeated exposure and practice, and the progression of memory problems that worsen over time rather than remaining stable.

In Alzheimer's disease, memory loss typically follows a characteristic pattern that begins with difficulty forming new memories while initially preserving older, well-established memories. Individuals may forget recent conversations, appointments, or events while maintaining clear recollection of childhood experiences, historical events, or long-established personal information. This pattern reflects the disease's initial impact on the hippocampus, the brain region crucial for forming new memories.

The progression of memory loss in Alzheimer's disease typically involves several stages, beginning with mild forgetfulness that may be attributed to normal aging or stress, progressing to more obvious memory problems that interfere with work or social activities, and eventually leading to severe memory impairment that affects personal identity, family recognition, and basic life skills.

Short-term memory problems often represent the earliest and most noticeable memory changes in dementia, including difficulty remembering recent conversations, appointments, or events that occurred within the past few hours or days. Individuals may repeat questions or stories, forget that they have already eaten meals, or fail to remember important information provided just minutes earlier.

Working memory, which involves the ability to hold and manipulate information in mind for brief periods, becomes impaired in dementia and affects the ability to follow complex instructions, perform mental calculations, or engage in conversations that require tracking multiple topics or ideas simultaneously. These working memory problems can significantly impact daily activities such as cooking, managing finances, or following medication schedules.

Episodic memory, which involves the recollection of specific personal experiences and events, becomes progressively impaired in dementia, leading to difficulty remembering recent experiences, conversations with family members, or participation in activities and events. This type of memory loss can be particularly distressing for families as individuals may not remember visits, phone calls, or shared experiences that are meaningful to loved ones.

Semantic memory, which involves general knowledge about the world, concepts, and facts, may be preserved longer in some types of dementia but eventually becomes affected as the condition progresses. Individuals may lose knowledge about common objects, concepts, or procedures that were previously automatic and well-established.

Procedural memory, which involves learned skills and habits such as driving, cooking, or personal care routines, may be preserved longer than other types of memory but eventually becomes impaired as dementia progresses. The loss of procedural memory can significantly impact independence and safety as individuals lose the ability to perform familiar tasks and activities.

The impact of memory loss on daily functioning represents a crucial factor in distinguishing normal aging from dementia. Memory problems that interfere with work performance, social relationships, or independent living suggest the need for professional evaluation and assessment. The progression and pattern of memory loss can also provide important diagnostic information that helps distinguish between different types of dementia and guide appropriate treatment approaches.

What Behavioral Changes Signal Dementia Onset?

Behavioral changes often represent some of the earliest and most distressing signs of dementia, yet they may be overlooked or attributed to other factors such as depression, stress, or normal personality changes associated with aging. Understanding the specific types of behavioral changes that can signal dementia onset enables families to recognize when professional evaluation may be needed and helps distinguish dementia-related changes from other conditions that may cause similar symptoms.

Personality changes represent one of the most significant behavioral indicators of dementia, particularly in frontotemporal dementia where personality alterations may precede memory problems by several years. These changes often involve a fundamental shift in the individual's core personality traits, values, and social behavior that represents a marked departure from their lifelong patterns and characteristics.

Loss of empathy and social awareness can manifest as insensitivity to others' feelings, inappropriate comments or behavior in social situations, or failure to recognize social cues that would normally guide behavior. Individuals may make hurtful or embarrassing comments without apparent awareness of their impact, engage in inappropriate physical contact, or violate social norms in ways that are completely out of character.

Increased impulsivity and poor judgment may become apparent through reckless spending, inappropriate sexual behavior, dangerous driving, or other actions that demonstrate a loss of the normal inhibitions and decision-making processes that guide behavior. These changes can create significant safety concerns and legal or financial problems for individuals and their families.

Apathy and loss of motivation often develop early in dementia, manifesting as decreased interest in previously enjoyed activities, reduced initiative in starting or completing tasks, and general withdrawal from social and recreational pursuits. This apathy differs from depression in that individuals may not express sadness or distress about their reduced activity level, instead showing a general lack of concern or motivation.

Agitation and irritability may increase significantly in individuals with dementia, particularly in response to situations that involve confusion, frustration, or overstimulation. These behavioral changes may be triggered by specific circumstances such as changes in routine, unfamiliar environments, or attempts to assist with personal care, but may also occur without obvious precipitating factors.

Repetitive behaviors and obsessions can develop in dementia, including repetitive questions, actions, or movements that may serve to reduce anxiety or provide comfort in the face of cognitive confusion. These behaviors may include repeatedly checking locks or appliances, asking the same questions multiple times, or engaging in repetitive physical movements such as pacing or hand-wringing.

Sleep disturbances and changes in daily rhythms often accompany dementia and can significantly impact behavior and mood. These may include difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep, excessive daytime sleepiness, confusion about day and night, or complete reversal of normal sleep-wake cycles that can be extremely challenging for caregivers.

Wandering and restlessness represent common behavioral changes in dementia that can create significant safety concerns. Individuals may feel compelled to walk or move constantly, may attempt to leave their home or care facility, or may become lost in familiar environments due to confusion about their location or purpose.

Changes in eating behavior can signal dementia onset and may include loss of appetite, forgetting to eat, eating inappropriate items, or dramatic changes in food preferences. Some individuals may lose interest in food entirely, while others may develop cravings for sweets or may eat excessively without awareness of satiety.

Paranoia and suspiciousness may develop as individuals with dementia struggle to understand and remember events, leading them to blame others for misplaced items, forgotten appointments, or other problems. These paranoid thoughts can strain family relationships and create additional stress for both the individual and their caregivers.

Inappropriate sexual behavior can occur in some forms of dementia, particularly frontotemporal dementia, and may include inappropriate comments, touching, or public displays that violate social norms. These behaviors can be extremely distressing for families and may require specialized management strategies and environmental modifications.

The timing and pattern of behavioral changes can provide important diagnostic information, as different types of dementia tend to produce characteristic behavioral profiles. Frontotemporal dementia typically involves early and prominent personality and behavioral changes, while Alzheimer's disease may initially present with more subtle behavioral alterations that become more pronounced as the condition progresses.

Understanding that behavioral changes in dementia result from brain pathology rather than willful misconduct helps families respond with appropriate compassion and seek professional guidance for management strategies. These changes often represent the individual's attempt to cope with confusion, fear, or frustration related to their cognitive decline, and appropriate interventions can help reduce distressing behaviors while maintaining dignity and quality of life.

When Should You Seek Medical Advice for Dementia Symptoms?

Determining when to seek medical advice for potential dementia symptoms can be challenging, as the early signs of cognitive decline may be subtle and develop gradually over months or years. However, early evaluation and diagnosis provide important benefits, including access to treatments that may slow progression, opportunities for planning and preparation while the individual can still participate in decision-making, and connection to support services and resources that can help families navigate the challenges of cognitive decline.

The decision to seek medical evaluation should be based on the presence of cognitive or behavioral changes that represent a significant departure from the individual's previous functioning and that interfere with daily activities, work performance, or social relationships. These changes should be persistent and progressive rather than temporary fluctuations that might be attributed to stress, illness, or other reversible factors.

Memory problems that warrant medical evaluation include difficulty remembering recent events, conversations, or appointments that interferes with daily functioning, repeated questions or stories that suggest the individual does not remember previous discussions, increasing reliance on memory aids or family members to manage previously independent activities, and getting lost in familiar places or having difficulty following familiar routes.

Changes in thinking and reasoning abilities that should prompt evaluation include difficulty with problem-solving, planning, or organizing activities that were previously routine, trouble managing finances, paying bills, or making appropriate financial decisions, problems following instructions or completing multi-step tasks, and confusion about time, place, or circumstances that goes beyond occasional disorientation.

Language and communication changes that warrant attention include difficulty finding words or following conversations, problems understanding written or spoken instructions, changes in writing ability or handwriting, and repetitive speech or loss of vocabulary that affects communication effectiveness.

Behavioral and personality changes that should trigger evaluation include significant alterations in personality, mood, or social behavior that represent a departure from lifelong patterns, loss of interest in previously enjoyed activities or social withdrawal, inappropriate social behavior or loss of social judgment, and increased anxiety, agitation, or other mood changes that cannot be attributed to other factors.

Functional decline that affects independence and safety represents an important indicator for medical evaluation, including difficulty performing activities of daily living such as bathing, dressing, or meal preparation, problems managing medications or medical care, safety concerns related to driving, cooking, or home maintenance, and increasing dependence on others for activities that were previously managed independently.

The timing of medical evaluation becomes particularly important when symptoms interfere with work performance, create safety concerns, or significantly impact family relationships and social functioning. Early evaluation allows for comprehensive assessment to rule out reversible causes of cognitive decline and to establish baseline functioning that can guide future care planning and treatment decisions.

Family members and friends often play a crucial role in recognizing the need for medical evaluation, as individuals with early dementia may lack awareness of their cognitive changes or may minimize their significance. Concerns expressed by multiple family members or friends about changes in thinking, behavior, or functioning should be taken seriously and prompt professional evaluation.

The choice of healthcare provider for initial evaluation may include the individual's primary care physician, who can conduct preliminary assessment and provide referrals to specialists if needed, a geriatrician who specializes in the medical care of older adults and has expertise in cognitive assessment, a neurologist who can evaluate neurological causes of cognitive decline, or a geriatric psychiatrist who can assess both cognitive and psychiatric aspects of behavioral changes.

Preparation for medical evaluation should include gathering information about the individual's medical history, current medications, and family history of dementia or other neurological conditions, documenting specific examples of cognitive or behavioral changes and their impact on daily functioning, bringing a list of current medications and supplements, and having a trusted family member or friend accompany the individual to provide additional information and support.

The importance of early evaluation extends beyond diagnosis to include opportunities for treatment and intervention that may be most effective in the early stages of cognitive decline, legal and financial planning while the individual can still participate in decision-making, family education and support to help navigate the challenges of cognitive decline, and connection to community resources and support services that can enhance quality of life for both the individual and their caregivers.

For families in West Virginia seeking comprehensive evaluation and specialized care for dementia symptoms, Braley Care Homes provides expert assessment and memory care services with experienced professionals who understand the complexities of different dementia types and can help families navigate the diagnostic process while providing appropriate support and care options throughout the progression of cognitive decline.

How Are Different Types of Dementia Diagnosed?

The diagnosis of dementia requires a comprehensive evaluation process that combines clinical assessment, cognitive testing, medical history review, and often specialized imaging or laboratory studies to distinguish between different types of cognitive impairment and rule out reversible causes of cognitive decline. The complexity of dementia diagnosis reflects the need to differentiate between various neurodegenerative conditions that may present with similar symptoms but require different treatment approaches and have different prognoses.

The diagnostic process typically begins with a detailed medical history that explores the onset, progression, and specific characteristics of cognitive and behavioral changes, along with review of current medications, medical conditions, and family history that may contribute to or explain cognitive symptoms. This history-taking process often involves both the individual and family members or close friends who can provide objective observations about changes in functioning and behavior.

Cognitive assessment represents a crucial component of dementia diagnosis and typically involves standardized tests that evaluate different domains of cognitive function, including memory, attention, language, executive function, and visual-spatial processing. The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) represent commonly used screening tools that provide a general assessment of cognitive function, while more detailed neuropsychological testing may be needed to characterize specific patterns of cognitive impairment.

Physical and neurological examination helps identify signs of other medical conditions that may contribute to cognitive decline and can reveal neurological abnormalities that suggest specific types of dementia. This examination may include assessment of reflexes, coordination, gait, and other neurological functions that can provide clues about the underlying pathology causing cognitive symptoms.

Laboratory testing typically includes blood tests to rule out reversible causes of cognitive decline such as thyroid dysfunction, vitamin deficiencies, infections, or metabolic abnormalities that can mimic dementia symptoms. These tests may include complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, thyroid function tests, vitamin B12 and folate levels, and other studies based on the individual's specific symptoms and medical history.

Brain imaging studies play an increasingly important role in dementia diagnosis and can help distinguish between different types of cognitive impairment while ruling out other conditions such as brain tumors, strokes, or normal pressure hydrocephalus. Computed tomography (CT) scans can reveal structural abnormalities, while magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides more detailed information about brain structure and can identify patterns of atrophy characteristic of specific dementia types.

Advanced imaging techniques such as positron emission tomography (PET) scans can provide information about brain metabolism and the presence of abnormal protein deposits characteristic of specific dementia types. Amyloid PET scans can detect the presence of amyloid plaques associated with Alzheimer's disease, while tau PET scans can identify tau protein tangles that characterize various neurodegenerative conditions.

Cerebrospinal fluid analysis may be recommended in certain cases to measure levels of proteins associated with Alzheimer's disease, including amyloid beta and tau proteins that can provide additional diagnostic information when clinical presentation is unclear or when early-onset dementia is suspected.

Genetic testing may be considered for individuals with early-onset dementia or strong family histories of neurodegenerative conditions, particularly for conditions such as Huntington's disease or familial forms of Alzheimer's disease where specific genetic mutations have been identified.

What Tests Are Used to Diagnose Alzheimer's Disease?

The diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease relies on a combination of clinical assessment, cognitive testing, and increasingly sophisticated biomarker studies that can identify the characteristic pathological changes associated with this condition. While definitive diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease traditionally required post-mortem examination of brain tissue, advances in imaging and biomarker technology now allow for more accurate diagnosis during life.

Cognitive assessment for Alzheimer's disease typically focuses on memory function, particularly the ability to learn and retain new information, which represents the hallmark cognitive impairment in this condition. Standardized memory tests such as the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-Cog) and the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale provide detailed evaluation of memory and other cognitive functions affected by Alzheimer's disease.

Neuropsychological testing can reveal the characteristic pattern of cognitive impairment in Alzheimer's disease, including prominent memory problems with relative preservation of other cognitive functions in early stages, followed by gradual decline in language, executive function, and visual-spatial processing as the condition progresses. This testing can help distinguish Alzheimer's disease from other forms of dementia that may present with different patterns of cognitive impairment.

Brain imaging studies for Alzheimer's disease diagnosis include structural MRI scans that can reveal the pattern of brain atrophy characteristic of this condition, particularly in the hippocampus and other medial temporal lobe structures that are affected early in the disease process. The degree and pattern of atrophy can provide important diagnostic information and help track disease progression over time.

Amyloid PET imaging represents a significant advance in Alzheimer's disease diagnosis, allowing for the detection of amyloid plaques in the living brain. These scans can identify the presence of amyloid pathology that characterizes Alzheimer's disease and can help distinguish this condition from other forms of dementia that do not involve amyloid accumulation.

Tau PET imaging is an emerging technology that can detect the presence of tau protein tangles in the brain, providing additional information about the pathological changes associated with Alzheimer's disease. The pattern and extent of tau pathology correlates more closely with cognitive symptoms than amyloid pathology, making tau imaging particularly valuable for understanding disease progression.

Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease include measurements of amyloid beta 42, total tau, and phosphorylated tau proteins that reflect the pathological changes occurring in the brain. Decreased levels of amyloid beta 42 combined with increased levels of tau proteins suggest the presence of Alzheimer's disease pathology and can support the diagnosis when clinical presentation is consistent with this condition.

Blood-based biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease represent an active area of research and development, with several promising tests that may eventually allow for simpler and more accessible screening and diagnosis. These blood tests measure various proteins and other molecules that reflect brain pathology and may provide valuable diagnostic information without the need for more invasive procedures.

The integration of clinical assessment, cognitive testing, and biomarker studies allows for more accurate diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease and can help distinguish this condition from other forms of dementia that may require different treatment approaches. Early and accurate diagnosis enables appropriate treatment planning and provides families with important information for future care planning and decision-making.

How Is Vascular Dementia Identified Through Imaging?

Brain imaging plays a crucial role in the diagnosis of vascular dementia, as it can directly visualize the vascular pathology that underlies this condition and distinguish it from other forms of dementia that may present with similar clinical symptoms. The ability to identify specific patterns of vascular damage helps confirm the diagnosis and guides appropriate treatment strategies focused on managing underlying cardiovascular risk factors.

Computed tomography (CT) scans represent the most basic imaging approach for identifying vascular dementia and can reveal evidence of strokes, including both large strokes that cause obvious neurological symptoms and smaller strokes that may have gone unnoticed clinically. CT scans can also identify chronic changes such as white matter lesions and brain atrophy that suggest chronic vascular disease affecting cognitive function.